–

陰符鎗譜

CONCEAL & REVEAL SPEAR

王宗岳

attributed to Wang Zongyue

[preface dated 1795, though the authenticity of the document is debatable, the most we can say for sure being that the text we have is coming from Tang Hao’s presentation of the manual, 1936]

[translation by Paul Brennan, Sep, 2023]

–

陰符鎗譜敍

PREFACE

蓋自易有太極始生兩儀而陰陽之義以名然道所宜一理百體而安萬化者則不存乎陽而存乎陰孔子曰尺蠖之屈以求伸之也龍蛇之蟄以存身也古今來言道家本乎此卽古今來談兵之家亦有未能出乎此者也每慨世之所謂善槊者類言勢而不言理夫宰勢而不言理是徒知有力而不知有巧也非精於技者矣

山右王先生自少時經史而外黃帝老子之書及兵家言無書不讀而兼通繫刺之術鎗法其尤精者也蓋先生深觀於盈虛消息之機熟悉於止齊步法之節簡練揣摩自成一家名曰陰符鎗噫非先生之深於陰符而能如是乎

辛亥歲先生在洛卽以示予予但觀其大略而未得深悉其蘊每以為憾予應鄕試居汴而先生適舘於汴退食之餘復出其舘示予乃悉心觀之先生之舘鎗其潛也若藏於九泉之下其發也若動於九天之上下無窮剛柔相易而其總歸於陰之一字此誠所謂陰符鎗者也夫理無大小道有淺深隨人所用皆可會於一源陰符經言道之書廣大悉備而先生取其一端用之一鎗然則觀之於鎗亦可知先生知於道矣昔楊氏之鎗自云二十年梨花鎗天下無敵手夫以婦人而明鎗法不過知其勢未必能達其理意也而猶能著一時而傳後世若此況先生深通三教之書準今析古精練而成而謂不足傳於天下後世乎

先生常謂予曰予本不欲譜但於悉心此中數十年而始少有所得不以公之天下亦鳥之於功若知其是哉於是將鎗法集成為訣而明其進退變化之法囑序於予因誌其大略而為之序云戟

乾隆歲次乙卯

[Quoting from the commentary to the Book of Changes:] “Change involves a grand polarity [tai ji], which produces the dual aspects,” referring to the passive and active aspects [yin / yang]. This art requires them both. Throughout the countless shapes and endless transformations, you must not become fixated on only the active aspect or only the passive aspect. Confucius said [again from the Book of Changes commentary]: “Inchworms bend to extend. Serpents hibernate to survive.” Ever since ancient times, Daoist philosophy has been based in such ideas, and military strategists have likewise not been able to do without them.

Whenever a generation proclaims a “spear master”, they overstate his technique and do not speak of his theory. To do so is to only know his power and not understand his skill, and therefore there is no comprehension of the essence of his art. Master Wang of Shanxi has read studiously ever since his youth, not just Confucian classics, but every book on Daoism and military strategy as well. He also has a thorough understanding of the arts of fighting with weapons, especially skillful in spear methods. He has deep insight into the waxing and waning of opportunity, and the intricate rhythms of footwork. After isolating essentials and contemplating them deeply, he has created his own art, calling it “Conceal & Reveal Spear”. Without developing profound skill in both concealing and revealing, he would not have been able to achieve this.

In 1791, Wang was in Luoyang. During his time there, he shared his art with me. Although I was able to grasp the general ideas, I did not obtain a thorough understanding of all its refinements, which I have regretted ever since. When I later went to Kaifeng for the provincial civil-service exams, Wang also happened to be staying there at the time. After finishing a meal together, he brought out his spear manuscript to show me. I examined it carefully and found that his spear art involves stealth that is as though [quoting from Art of War, chapter 4] “hidden below the deepest ground”, display that is as though “moving above the highest sky”, and alternating endlessly between the two states.

With hardness and softness changing into each other in this way, you will ultimately discover wisdom that had been hidden. It therefore truly lives up to its name of Conceal & Reveal. The theory is boundless and the method is profound. By acting in accordance with what the opponent is doing, you will always be able to connect with the original nature of existence. There is a Daoist text called “The Classic of the Concealed & Revealed” [Yin Fu Jing]. It points to the bigger picture, whereas Wang’s book focuses on only one simple thing: the wielding of a spear. However, it is clear from examining his spear book that his wisdom is fundamentally Daoist.*

There was previously the spear skill of Master Yang, who trained for twenty years at the Pear Blossom Spear and became invincible. He taught his wife the spear art. She only learned the postures and did not really get a firm grasp of the theory, but was nonetheless able to pass down the art. Master Wang has steeped himself in the literature of the three ancient traditions [Confucianism, Daoism, Buddhism], viewing the present through the eyes of the past, but this might make it somewhat difficult to pass down his art to future generations.

Wang once told me: “I didn’t originally intend to write a manual. However, after decades of meticulous practice, I feel I’ve obtained something worthwhile, and if I don’t share it with the world, there might never be anybody else who knows these skills.” Therefore he now presents his spear art in a collection of instructions, illuminating his methods of advancing, retreating, and adapting. He has urged me to write a preface to his manuscript in order to give a general sense of what lies herein.

- written by Wang’s student, 52nd year of the cycle, during the reign of Emperor Qianlong [i.e. 1795]

*[The main hint of the Daoist influence is of course the borrowing of the title in homage to the earlier text. An explanation for the title of the Classic appears in a commentary for it attributed to 張果 Zhang Guo:

觀自然之道,無所觀也。不觀之以目而觀之以心,心深微而無所見,故能照自然之性,其斯之謂陰。執自然之行,無所執也,不執之以手而執之以機,機變通而無所繫,故能契自然之理,其斯之謂符。照之以心,契之以機,而陰符之義盡矣。李筌以陰為暗,以符為合。

We see the way of nature without seeing it, seeing not with our eyes, but with our minds. When the mind contemplates deeply, it looks beyond sight, and thus we are able to discover the true character of nature. This is what is meant by the “concealed”.

We hold onto the activity of nature without holding it, holding not with our hands, but with our decisions. When our decisions are adaptive, they are not rigidly committed to, and thus we are able to behave in accordance with the principles of nature. This is what is meant by the “revealed”.

To discover by way of our minds and to be in accordance by way of our decisions – this is the entire meaning of “concealed and revealed”. The interpretation of Li Quan is even more succinct: “concealed” refers to what is invisible, and “revealed” refers to being in accordance with it.]

–

陰符鎗譜目錄

CONTENTS

一 陰符鎗訣六則

One: General Principles (six sections)

二 上平勢七則

Two: High Attacks (seven [six] scenarios)

三 中平勢十三則

Three: Mid-Level Attacks (thirteen scenarios)

四 下平勢十一則

Four: Attacks from Below (eleven scenarios)

五 穿袖挑手穿指搭外搭裏十七則

Five: Through the Sleeve, Carrying Hand, Threading Finger, Connecting Outward, Connecting Inward (seventeen sections)

六 陰符鎗七絕四首

Six: Four Verses of Seven-Character Lines

–

陰符鎗譜

CONCEAL & REVEAL SPEAR

–

一 陰符鎗總訣六則

ONE: GENERAL PRINCIPLES (six sections)

一身則高下手則陰陽步則左右眼則八方

1. Your body goes high and low.

Your hand grips are passive [one palm facing downward] and active [other facing upward].

Your steps zigzag side to side.

Your gaze goes all around.

二陽進陰退陰出陽囘粘隨不脫疾若風雲

2. Advance is active. Retreat is passive.

Once passive, then go forth. Once active, then withdraw.

Stick and follow without disconnecting.

Be as sudden as winds and storms.

三以淨觀動以退敵前審機識勢不為物先

3. Use stillness to await movement.

Use retreat to defeat advance.

Look for opportunity and recognize the situation.

Do not be the first to move.

四下則高之高則下之左則右之右則左之

4. If the opponent goes low, go high.

If he goes high, go low.

If he goes left, go right.

If he goes right, go left.

五剛則柔之柔則剛之實則虛之虛則實之

5. If the opponent hardens, soften.

If he softens, harden.

If he fills, empty.

If he empties, fill.

六鎗不離手步不離拳守中禦外必對三尖

6. The spear techniques do not depart from boxing principles.

The stepping does not depart from that of the boxing techniques.

Defend your center by warding away all threats.

You must align the three points [spear tip, front toes, nose].

–

二 上平勢七則

TWO: HIGH ATTACKS (seven [six] scenarios)

立身要聳前步要顚滿托上與胸齊此長鎗勢也用之小鎗可也

[1] Standing straight and tall, my front foot stomps down as I prop up fully at chest level. This is a long spear posture, but can also be performed using a short spear.

彼鎗扎我左脅我開左步向裏促步前進連掤他手勢窮反鎗我單手扎出

[2] The opponent stabs to my left ribs. I step out with my left foot, hastening a step to advance to the inside, while warding away his hand. Once my posture has finished, my spear has turned over, and I send out a single-hand stab.

彼鎗扎我右脅我開右步向外隨步扎彼小門落騎馬勢卽照下平勢運用可也

[3] The opponent stabs to my right ribs. I step out with my right foot, follow it with my left foot, then come down with my right foot into a horse-riding stance, I stab to his small gate. [The text unfortunately does not define the terms “small gate” and “large gate”.] This can also be performed as a low stab.

彼鎗扎高我大門我搭鎗如蛇纏物連足赶上二轉將彼鎗扶在正中盡力使下卽用單手扎出小門同

[4] The opponent stabs high to my large gate. I use my spear to connect to his spear like a snake coiling around an animal, my feet each stepping forward as I wrap around his weapon twice, keeping his spear at mid-level, then forcing it down, and then I send a single-hand stab to his small gate.

彼從大門不論上中下三門扎我卽乘扎之時開右步隨右步躱開彼鎗用單手盡力中平扎彼大門是為靑龍獻爪

[5] The opponent attacks my large gate, stabbing me either high, middle, or low. Taking advantage of the moment he stabs, I step out with my right foot and move onto it to evade his spear while forcefully sending a single-hand stab to his large gate. This technique is called BLUE DRAGON PRESENTS A CLAW.

彼從小門不論上中下三門扎我卽乘彼鎗之時懸空轉步躱開彼鎗用單手盡力扎彼小門亦是靑龍獻爪

[6] The opponent attacks my small gate, stabbing me either high, middle, or low. Taking advantage of the timing of his technique, I leap and switch my feet to evade his spear while forcefully sending a single-hand stab to his small gate. This is also called BLUE DRAGON PRESENTS A CLAW.

–

三 中平勢十三則

THREE: MID-LEVEL ATTACKS (thirteen scenarios)

立身要正平鎗在臍上彼中平扎我大門我用圈法圈開彼鎗單手扎出

[1] I stand straight with my spear held level over my navel. The opponent does a mid-level stab to my large gate. I use a coiling method to coil aside his spear, then send out a single-hand stab at him.

彼中平扎我小門我用圈法圈開彼鎗單手扎出可也

[2] The opponent does a level stab to my small gate. I use a coiling method to coil aside his spear, then send out single-hand stab.

彼鎗中平扎我大門我退步掩彼鎗稍彼轉扎我小門我撒前手單手扎彼小門

[3] The opponent does a level stab to my large gate. I retreat and cover his spear tip. He switches to stabbing to my small gate. I let go with my front hand and send a single-hand stab to his small gate.

彼中平扎我小門退步掩彼鎗稍彼鎗扎我大門我撒前手單手扎出可也

[4] The opponent does a level stab to my small gate. I retreat and cover his spear tip. He now stabs to my large gate. I let go with my front hand and send out a single-hand stab.

彼中平扎我大門我開左步隨右步後手轉陽至臍下前手合陰雙手照他虎口扎出

[5] The opponent does a level stab to my large gate. I step out with my left foot, following it with my right foot. My rear hand turns over so the center of the hand is facing upward below my navel, my front hand covering so the palm is facing downward, and I send a double-hand stab to the tiger’s mouth of his front hand.

彼中平扎我小門我開左步隨右步落騎馬勢雙手照他手腕扎去

[6] The opponent does a level stab to my large gate. I step out with my left foot, following it with my right foot, my left foot coming down into a horse-riding stance, and send a double-hand stab to his wrist.

彼中平扎我大門我用靑龍獻爪扎去與上平法同彼扎我小門我用靑龍獻爪扎去亦與上平法同

[7] The opponent sends a level stab to my large gate. I stab out with BLUE DRAGON PRESENTS A CLAW, same as in the high attack scenarios. Or if he stabs to my small gate, I can still stab out with the same technique.

彼中平扎我大門我退步挑彼手腕鎗要出長前手仰後手合

[8] The opponent does a level stab to my large gate. I retreat and do a carrying action to his wrist. My spear should reach out long. My front hand is gripping with the palm facing upward, rear hand with the palm facing downward.

彼中平扎我大門我退步從他指前手托後手扎

[9] The opponent does a level stab to my large gate. I retreat from him, pointing with my front hand, propping up with my rear hand, and send out a stab.

彼高扎我大門我隨鎗作托刀勢起鎗扎彼手或彼桿或彼鎗開稍卽反手用盡力扎出

[10] The opponent does a high stab to my large gate. I respond by wielding my spear in a “saber carrying” posture, lifting my spear to stab to his hand, prop up his spear shaft, or take aside his spear tip. Then I turn over my hands and forcefully send out a stab.

彼高扎我圈開彼鎗進步雙手高扎彼臉他鎗起護我撒開前手用單手扎彼腮

[11] The opponent does a high stab at me. I coil his spear aside, then advance and do a high double-hand stab to his face. His spear lifts to shield it. I let go with my front hand and do a single-hand stab to his cheek.

彼平扎我小門我開左步隨右步落騎馬勢捉彼以後照彼下平勢用

[12] The opponent does a level stab to my small gate. I step out with my left foot, following it with my right foot, my left foot coming down into a horse-riding stance, my spear catching his and then attacking him with a low stab.

彼待鎗不動如先扎必合鎗開稍則扎不開稍則不扎

[13] The opponent waits with his spear unmoving, as if to stab me first. I must use my spear to smother his spear and take the tip aside, then stab. If I do not send his tip aside, I will not be able to stab.

–

四 下平勢十一則

FOUR: ATTACKS FROM BELOW (eleven scenarios)

彼中平梨花滾袖鎗扎我我用陰陽手一仰一合輕敲彼鎗連足退後要扎他他轉鎗之時我撒前手單手扎出

[1] The opponent stabs at me with the Pear Blossom Spear technique of “rolling sleeves” at mid-level. With my hands placed one palm facing upward, the other facing downward, I lightly knock away his spear while my feet successively retreat, positioning myself in readiness to send out a stab. As he coils his spear around, I now let go with my front hand and send out a single-hand stab.

彼低粘我不論大小門我與他落鎗之時進前步起身扎他咽喉此下平勢俱可用之

[2] The opponent uses his spear to stick to mine from underneath, whether large gate or small gate. Then as he lowers his spear, I advance, rising up, and stab to his throat. Or I could use a low stab, either way is fine.

托刀勢後腿弓前腿蹬彼扎我我身懸空轉步單手扎彼腳腕

[3] In a “saber carrying” posture, with his rear leg bent, front leg straight, the opponent stabs at me. I jump up, switch feet, and send out a single-hand stab to his wrist.

彼從大中平扎我我前足收囘用雙手扎俯身打彼鎗桿連足赶上敲彼前手待彼勢窮反鎗單手扎出

[4] The opponent attacks my large gate with a level stab. With my front foot withdrawing, I send out a double-hand stab. Then lowering my body, I strike down his spear shaft and pursue him with successive steps while knocking at his front hand. I wait until he halts his retreat, then I turn over my spear and send out a single-hand stab.

彼從小門斜扎我我將前足收囘用陽手背扎扎他鎗彼轉鎗大門扎我我開左步代右步用單手扎彼小腹

[5] The opponent attacks my small gate, stabbing at me diagonally. I withdraw my front foot and send out a stab with the back of my front hand facing upward, stabbing at his front hand. He coils his spear and stabs to my large gate. I step out with my left foot, then switch to my right foot, while sending out a single-hand stab to his lower abdomen.

彼低粘我鎗我向他小門開左步促右步雙手扎彼乳下

[6] The opponent sticks to my spear from underneath. Aiming toward his small gate, I step out with my left foot, hasten forward with my right foot, and do a double-hand stab below his chest.

我稍在左他中平扎我我開左步代右步單手盡力扎彼小腹

[7] While my spear tip is pointing out to the left, the opponent sends out a level stab at me. I step out with my left foot, then switch to my right foot, and forcefully do a single-hand stab to his lower abdomen.

我鎗在右他中平扎我我懸空轉步洛騎馬勢單手扎彼左脅中與不中卽抽鎗照原勢跳囘

[8] While my spear tip is pointing out to the right, the opponent sends out a level stab at me. I jump up, switch my feet, come down into a horse-riding stance, and do a single-hand stab to his left ribs. I am on target but not quite on target, and so I immediately draw back my spear to its original carrying position.

他若赶來將鎗在地顚起用滑步扎他我鎗稍在中看其身一動卽發鎗扎去是謂先發制人名占位之鎗

[9] If the opponent chases me, I lift my spear tip up to mid-level and send out a stab while using a sliding step to charge into him. Once I see his body move, I am already stabbing with my spear. This is an example of [quoting from Book of Han, bio of Chen Sheng & Xiang Yu:] “the first to act controls the other [whereas the last to act is controlled by the other]” and is called the “throne seizing” spear technique.

彼從大門高扎我我從大門圈開他鎗用單手扎出可也

[10] The opponent attacks my large gate with a high stab. I likewise follow into his large gate to coil aside his spear and can then do a single-hand stab.

彼從小門高扎我我從小門圈開彼鎗亦用單手出也

[11] The opponent attacks my small gate with a high stab. I likewise follow into his small gate to coil aside his spear, and again can then do a single-hand stab.

–

五 川袖挑手穿脂搭外搭裏十七則

FIVE: THROUGH THE SLEEVE, CARRYING HAND, THREADING FINGER, CONNECTING OUTWARD, CONNECTING INWARD [terms which confusingly go undefined and unused] (seventeen sections)

一今人扎鎗步步上前殊失進退之理我今定退一步法隨護隨退則彼鎗扎空其心必亂亂而取之其勢甚易蓋爭先者黄帝之學也退後者老子之教也

1. If when the opponent stabs out, he steps ever more forward, he has especially forgotten the principle of advance and retreat. And so I take a stable step back, guarding as I retreat. Thus his spear misses and his mind falls into confusion. In his confusion, I take control, his posture so easily changed. To strive to be first is the learning of the Yellow Emperor. To step back is the teaching of Laozi.

二今人扎鎗以捉拿為主捉拿不住不敢還鎗則利在常扎者不如躱還只妙在一時所謂中平一點難招架也

2. When the opponent stabs with his spear, the most important thing is to grab it with my own. If I do not catch it firmly, I will not dare to counter. The advantage lies in being the one who is always attacking, rather than defending and countering, which can only be briefly effective. Thus it is said that a middle height technique [being able to respond more quickly in any direction than a high or low one] is more difficult to parry.

三今人扎鎗高扎高迎低扎低迎緊緊相隨為恐不及失之大迂不如高扎高迎彼洛我卽扎高低扎低迎彼起我卽扎低在上扎上在下扎下甚為捷便

3. When the opponent stabs, his high stab is received high, his low stab received low. I tightly follow along with what he is doing, fearing only to disconnect, of losing track of his winding path. Inferior to receiving a high stab high is to stab high when he lowers, and inferior to receiving a low stab low is to stab low with he lifts up. To stab above when above or below when below is quicker and more efficient.

四今人扎鎗多用轉鎗裏掩扎外外掩扎裏如梨花滾袖鎗是也不知此最吃虧如彼鎗扎我我從大門掩住彼鎗令其扎我小門彼轉鎗扎我我撒前手後手扎出彼洛空我鎗著實矣

4. When the opponent stabs, I often employ switching between actions, for instance covering inward and then stabbing outward, or covering outward and then stabbing inward, as in the Pear Blossom Spear technique of “rolling sleeves”, for he does not understand how very effective this will be. If he stabs at me, I move into his large gate to cover his spear, causing him to stab to my small gate, and when he stabs at me, I let go with my front hand and stab out with my rear hand. His attack thus lands on nothing, and my spear lands true.

五凡發鎗扎人遷扎透不遷扎穿一點便囘隨立一備不虞兵法所謂一克如始戰者是也愼之愼

5. Whenever I shoot out my spear to stab the opponent, it should be penetrating, not merely a threading action. And when I withdraw it, I should immediately be prepared against whatever may follow. It says in the military literature [Wuzi, chapter 4]: “Treat the end of a battle as no different from the beginning.” Do not let your guard down.

六凡與人扎對鎗不許呆立他以虛鎗相試我以虛鎗相應彼進我退彼退我進足要輕步要碎身無定影飄飄如仙待實扎之時我躱鎗還鎗使開步法向前偏身著力也

6. When fighting with spears, I must not stand stiffly. While the opponent uses feinting techniques to try me out, I in turn respond with feints to test him. When he advances, I retreat. When he retreats, I advance. The steps should be light and the stances should be temporary. My body does not settle, it wanders around like one of the immortals. I wait for a genuine stab to come, then I dodge his spear and I counter, inducing me to step forward, using the power of my whole body.

七凡與人對鎗要去貪心絕氣眼注彼手勿得旁觀微有不便不勉強發鎗待時而動一擊便為上乗

7. In spear fighting, I should not be greedy or angry. I keep my gaze upon the opponent’s hands, not looking around. Whenever there is the slightest difficulty, I do not force my way through with a stab, instead I wait for the right moment and then act. Attacking when it is easiest to do so is the best way.

八凡與人對鎗要善賣破綻誘之便入中途擊之彼不及防兵法所謂形之敵必從之者也

8. In spear fighting, I have to be good at advertising openings in order to lure the opponent in. Then once he gets halfway into his attack, he neglects his own defense. As it says in the Art of War [chapter 5]: “Adjust the position in such a way that it forces the opponent to comply.”

九凡與人對鎗我心不肯先扎必不得已亦為點一鎗誘之使入矣

9. In spear fighting, I should not be willing to stab first. The opponent then has no choice but to initiate. I merely lower my spear tip and lure him in.

十凡與人對鎗讓我先扎我虛點一鎗卽便囘身彼若赶來其舉足未定之時所謂及其陳未定而薄之者是也

10. When fighting with spears, if the opponent allows me to stab first, I feint a tap with my spear, then withdraw. If he chases to attack, I then take advantage of the moment when he lifts his foot but has not yet stepped down. This is called “weakening him before he stabilizes his position”.

十一凡與人扎鎗利在乘虛如彼扎上則下虛扎下則上虛扎右則左虛扎左則右虛以目注之以時蹈則上虛扎右則左虛扎左則右虛以目注蹈百不失一兵法兵形避實而擊者是也

11. When fighting with spears, advantage lies in taking advantage of gaps, for instance: when the opponent stabs above he becomes open below, when he stabs below he becomes open above, when he stabs to the right he becomes open on the left, when he stabs to the left he becomes open on the right. By gazing intently with my eyes and stepping at the right moment,* I will then not miss even once in a hundred attempts. It says in the Art of War [chapter 6]: “Avoid where the enemy’s position is full and attack where it is empty.”

*[The text at this point redundantly repeats “he becomes open above, when he stabs to the right he becomes open on the left, when he stabs to the left he becomes open on the right. By gazing intently with my eyes and stepping”. This suggests that the text was perhaps copied out rather than written mindfully, possibly indicating that the document may itself be a copy rather than an original text.]

十二凡與人扎鎗與用兵相吾體者兵也心者大將也目者先鋒也三軍運用雖在一人然平日之節制已戰之時先鋒領衆對敵固不及事事而謀之大將扎鎗亦然平日手是習熟對敵之時目光一照四休從今亦及著著用心也

12. When fighting with spears, these military analogies are useful: the body is an army, the mind a general, the gaze a vanguard. A single body is a full military force and always has to be treated as such. In battle, the vanguard leads the rest of the army to the enemy, yet the strategizing of the general is of more importance. This is also true in the daily training of hands and feet for spear fighting. When facing an opponent, the eyes show the way, the limbs follow, and the mind dictates every action.

十三凡扎鎗不必著數太多博而不精終屬無益只在要緊處操演精熟變化無窮而已所謂兵不在多而在精者也

13. When stabbing with the spear, it is not necessary to do many stabs. Quantity does not mean quality and would not amount to any meaningful advantage. What matters is to drill the techniques to the point of skill and then transform endlessly. As it is said [from Quelling the Demons’ Revolt, chapter 38]: “Armies win by skill, not by numbers. [And generals win by strategy, not by bravery.]”

十四凡與人扎鎗我發鎗扎彼彼從大門拿開我鎗洛左不必著急看其高來我倒後步盡力一抽洛抱刀勢反身單手扎出看其低來我倒後步作羣攔勢逼住他鎗

14. When fighting with spears, if I stab at the opponent and he enters my large gate to grab my spear and take it aside, I lower my spear to the left. I do not need to be in a hurry. If I see his attack is high, I retreat, forcefully withdrawing, and come down into a “saber carrying” posture, then turn around and perform a single-hand stab. If I see his attack is low, I retreat into a “crowd blocking” posture to force away his spear.

十五凡與人對鎗我發鎗扎人彼從小門拿開我鎗令我洛右不必著急待其扎來不論高低我將前步一退後手一提作剪步而走出險之後重囘定勢

15. When fighting with spears, if I stab at the opponent and he enters my small gate to grab my spear and take it aside, I lower my spear to the left. I do not need to be in a hurry, I just wait for his attack to come, be it high or low, then I retreat my front foot and lift my rear foot to evade with scissor steps, and once out of danger, I return again to a stable posture.

十六凡與人對鎗要看勢兵法云用衆者務易用寡者務險一人與二人扎鎗其數已陪況多者乎據險固不待言然平人扎鎗與兵究竟不同兩軍對壘限於紀律豈曳兵而走是平入則不然相待於城邑院落之中固宜或據穿口或據隘巷芳平原壙野彼衆我寡則以剪跳為主必不可背陷重圍想起空間之處卽我拖足之所彼趕來拖刀而走不趕卽止頻頻囘顧見有輕足善足者迫近吾身我囘身單手直刺中與不中拔鎗又走出險又息駡之使來趕來又如前如此則一可敵百矣

16. When fighting with spears, I have to observe the situation. It says in the military literature [Wuzi, chapter 5]: “When using a large force, take advantage of open ground. When using a small force, take advantage of confined ground.” When fighting against two opponents, they have numeric advantage, and much more so if there are many more of them. Maintaining strategic positions is not necessary, for when civilians fight with spears, it is actually different from soldiers. When armies face each other, they are held there by discipline, unable to run away. But this is not the case for ordinary people. Fighting within urban courtyards is a matter of doorways and narrow alleys rather than wide open spaces. If I am outnumbered, I concentrate on using scissor-step leaps, for I absolutely must not be backed into a corner or surrounded. I seek to stand in an open space, then if they give chase, attacking with their spears, I run. If they do not chase, I halt, constantly looking around. If I see that their steps are light and quick, and they are getting close to me, I turn around and perform single-hand stabs. I may hit some and miss some, then pull up my spear and run, and once I am out of danger, I stop. Then I curse at them to make them attack, and when they chase to attack, I repeat as before. In this way [i.e. gradually whittling down opponents], one can defeat a hundred.

十七凡與人扎鎗之法先學蹤跳能踰高趕遠繼之以則萬將難敵矣

17. In order to use stabbing techniques in spear fighting, it is necessary to first learn lunging. I will thereby be able to reach higher and farther, thus constantly making things more difficult for the opponent.

–

六 陰符鎗七絕四首

SIX: FOUR VERSES OF SEVEN-CHARACTER LINES

嫋嫋長鎗定二神也無他相也無人勸君莫作尋常看一段靈光貶此身

心須望手手望鎗望手望鎗總是真煉到丹成九轉後心隨鎗手一齊迷

至道何須分大小精粗總是一源頭若將此術兵論孫武何須讓一籌

靜處為陰動則符工夫祗是有沉謀若還靜裏無消息動似風雲也算浮

To skillfully wield the long spear, there are two constant mentalities:

no opponent, no self.

I urge you not to pose, just look ordinary,

and yet have a sense that an ethereal light is filling your whole body and causing your shape to blur.

The mind must urge the hand, and the hand must urge the spear,

and by way of this process of urging, everything will be correct.

After smelting internal elixir through many repetitions,

your mind, hand, and spear will all be moving in unison.

Ultimately the method does not need to be divided into a greater way or a lesser way.

Fineness and coarseness both come from the same source.

If you approach this art according to military theory,

Sunzi will not need to retract a single strategy.

When in stillness, you conceal. Once in motion, you reveal.

Skill is simply a matter of sinking down and scheming.

If you can return to stillness within and give nothing away,

your movement will seem like clouds carried by wind, making the opponent think that you are merely floating.

–

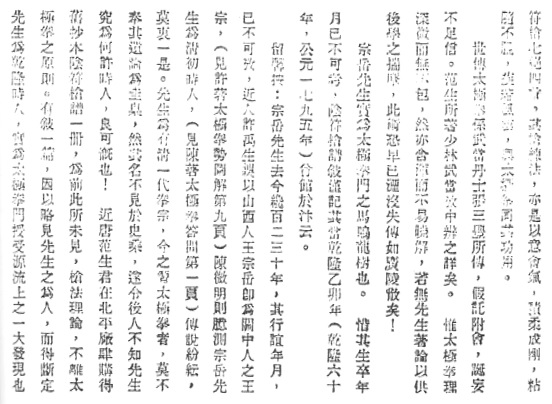

[Tang Hao unfortunately shared only one image from this booklet, meaning that for the rest of the text, we are left to trusting his transcription. He provided this image simply to prove that the unique spear material he had obtained really was immediately followed by the list of movements from the Chen family’s spring & autumn halberd set and the Taiji Classics. This image is of the booklet spread open to show two pages, which are about two thirds of the way through it, and if consistent to the format seen here would probably have been about thirty pages long.]

[The three lines on the right give a glimpse from the third and fourth of the Four Verses.]

春秋刀

SPRING & AUTUMN HALBERD

關聖提刀上霸橋

[1] GUAN YU LIFTS HIS HALBERD on the Bahe River bridge.

白雲蓋頂逞英儫

[2] CLOUDS COVER THE HEAD indicates a hero.

上三刀嚇殺許褚

[3] With THREE UPWARD CUTS, he frightens Xu Chu to death.

下三刀驚退曹操

[4] With THREE DOWNWARD CUTS, he scares away Cao Cao.

白猿托刀往上砍

[5] WHITE APE CARRIES THE HALBERD chops through the upper area.

一掤虎就地非來

[6] SPRINGING TIGER launches itself from the ground.

分鬃刀難遮難擋

[7] SWINGING THE BLADE SIDE TO SIDE is very difficult to block.

十字刀劈懷胸膛

[8] CROSS-SHAPED HALBERD chops through his chest.

〔翻身一刀往上砍〕

[9 – TURNING AROUND WITH THE HALBERD chops through the upper area.]

磨腰刀古樹盤根

[10] SLASHING TO THE WAIST withdraws to finish like an old tree’s twisted roots.

左插花往上急砍

[11] LEFT INSERTING FLOWERS quickly chops through the upper area.

舉刀磨旗懷抱月

[12] RAISE THE HALBERD LIKE WAVING A BANNER, then EMBRACE THE MOON.

舞花撒手往上騰

[13] FLOURISH AND LET GO WITH ONE HAND acts suddenly above,

落在懷中又抱月

[14] then bring the halberd down to again EMBRACE THE MOON.

起刀反身往上沖

[15] LIFT THE HALBERD WHILE TURNING AROUND thrusts through the upper area.

刺囘一舉嚇人魂

[16] To STAB OUT AND IMMEDIATELY WITHDRAW will scare the enemy to death.

插花往左定

[17] ROLLING FLOWERS TO THE LEFT…

[The text cuts off here because it has come to the end of the page and there is obviously a leaf missing between the two pages shown. Tang provides the rest of the halberd text based on Chen Village records.]

翻花往左定下勢

[17] ROLLING FLOWERS TO THE LEFT plants and sinks down.

白雲蓋頂又轉囘

[18] CLOUDS COVER THE HEAD turns you around.

右插花翻身往上砍

[19] RIGHT INSERTING FLOWERS turns around and chops through the upper area.

再舉靑銅砍死人

[20] LIFTING THE RUSTED BRONZE ends with chopping him to death.

翻花往左定下勢

[21] ROLLING FLOWERS TO THE LEFT plants and sinks down.

白雲蓋頂又轉囘

[22] CLOUDS COVER THE HEAD turns you around.

接袍翻身猛囘頭

[23] CLOSING THE ROBE involves turning around with a fierce look in the eyes.

十字分鬃直扎去

[24] SWINGING SIDE TO SIDE INTO A CROSSED SHAPE stabs straight out.

花刀轉下銅翻杆

[25] TWIRL THE HALBERD DOWNWARD like a bronze pole rolling over.

左右插花誰敢拒

[26] LEFT & RIGHT INSERTING FLOWERS will make none dare to oppose you.

花刀轉下鐵門閂

[27] TWIRL THE HALBERD DOWNWARD to be like an iron bar sealing a door.

捲簾倒退誰遮閉

[28] With ROLLING UP THE SCREEN, STEPPING BACK, none will think to block what is coming.

花左右往上砍

[29] FLOURISH THE HALBERD TO THE LEFT & RIGHT chops through the upper area.

十字一刀忙舉起

[30] After placing the CROSS-SHAPED HALBERD, quickly rise up.

春秋刀遇五關內

This is the kind of spring & autumn halberd skill that guarded the passes north and south, east and west, and in the center.

–

先師張三豐王宗岳傳留太極十三勢論

WANG ZONGYUE’S TRANSMISSION OF ZHANG SANFENG’S TAIJI THIRTEEN DYNAMICS TREATISE

一舉動週身俱要輕靈尤須貫串氣宜鼓盪神宜內練無使有缺陷處無使有高低處無使有斷續處其根在於腳發於腿主宰於腰行於手指由腳而腿而腰總須玩整一氣向前退後乃得機得勢有不得機得勢處身便散亂其病必於腰腿求之上下前後左右皆然凡此皆是意不在外面有上卽有下有左卽有右如意要向上卽於下意若將物掀起而加以挫之之意斯其根自斷乃壞之速而無疑虛實宜分淸楚一

Once there is any movement, the entire body should be nimble and alert. There especially needs to be connection from movement to movement. The energy should be roused and the spirit should be collected within. Do not allow there to be cracks or gaps anywhere, peaks or valleys anywhere, breaks in the flow anywhere.

Starting from the foot, issue through the leg, directing it at the waist, and expressing it at the fingers. From foot through leg through waist, it must be a fully continuous process, and whether advancing or retreating, you will then catch the opportunity and gain the upper hand. If you miss and your body easily falls into disorder, the problem must be in the waist and legs, so look for it there. This is always so, regardless of the direction of the movement, be it up or down, forward or back, left or right. And in all of these cases, the problem is a matter of your intention and does not lie outside of you.

With an upward comes a downward, with a left comes a right. If your intention wants to go upward, then harbor a downward intention. For example, when you pull a plant out of the ground, you first have to add a breaking intention, thereby easily snapping its root. In this way, it is broken off more efficiently and assuredly.

Empty and full must be distinguished clearly. In each part,… [the page in the image cutting off here]

處自有一處虛實處處總此宜虛實週身節節貫串勿令毫絲間斷耳

there is automatically a part that is empty and a part that is full. Everywhere it is always like this, an emptiness and a fullness. Throughout the body, as the movement goes from one section to another, there is connection. Do not allow the slightest break in the connection.

–

山右王宗岳先師太極拳論 一名長拳一名十三勢

WANG ZONGYUE OF SHANXI’S TREATISE ON TAIJI BOXING (ALSO CALLED LONG BOXING OR THIRTEEN DYNAMICS)

太極者無極而生陰陽之母也動之則分靜之則和無過不及隨曲就伸人剛我柔謂之走我順人背謂之粘動急則急應動緩則緩隨雖變化萬端而理為一貫由著熟而漸悟懂勁由懂勁而階及神明然非用力不能豁然貫通焉須領頂勁氣沉丹田不偏不倚忽隱忽現左重則左虛右重則右虛仰則彌高俯則彌深進之則欲長退之則欲促一羽不能加蠅蟲不能落人不知我我獨知人英雄所向無敵蓋皆由此而及也斯致旁門甚多雖勢有區別槪不外乎壯欺弱慢讓快耳有力打無力手慢讓手快是皆先天自然自能非關學力而有為也察四兩撥千斤之句顯非力勝觀耄耋能禦衆之形快何能為立如平準活似車輪偏沉則隨雙重則滯每見數年純工不能運化者率皆自為人制雙重之病未悟耳惟欲避此病須知陰陽粘卽是走走卽是粘陰不離陽陽不離陰陰陽相濟方為懂勁懂勁後愈練愈精默識揣摩漸至從心所欲本是捨己從人多悟捨近求遠所謂差之毫釐謬之千里學者不可不詳辦巫是為論

A grand polarity [tai ji] emerges from a state of nonpolarity [wu ji] and generates the passive and active aspects [yin / yang]. When there is movement, passive and active qualities become distinct from each other. When there is stillness, they return to being indistinguishable.

Neither going too far nor not far enough, comply and bend, then engage and extend. He applies hardness, so I use softness – this is yielding. I follow him when he backs off – this is sticking. If he moves fast, I quickly respond, and if his movement is slow, I leisurely follow. Although there is an endless variety of possible scenarios, this principle remains constant throughout.

Once you have ingrained these techniques, you will gradually come to the point that you are identifying energies, and then from there you will work your way toward something miraculous. But without a great deal of practice, you will never have a breakthrough.

Forcelessly press up your headtop. Sink energy to your elixir field. Do not lean in any direction. Suddenly vanish and suddenly appear. When there is pressure on my left, my left empties. When there is pressure on my right, my right empties. When he goes high, I go higher. When he goes low, I go lower. When he advances, I draw back farther than he can reach. When he tries to retreat, I crowd him ever closer. A feather cannot be added and a fly cannot land. The opponent does not understand me, only I understand him. A hero is one who encounters no opposition, and it is through this kind of method that such a condition is achieved.

There are many other schools of boxing arts besides this one. Although the postures are different between them, they generally do not go beyond the strong bullying the weak and the slow yielding to the fast. The strong beating the weak and the slow submitting to the fast are both a matter of inherent natural ability and bear no relation to skill that is learned. Examine the phrase “four ounces diverts a thousand pounds”, which is obviously nothing to do with abundance of strength. Or consider the sight of an old man repelling a group, which could not come from an aggressive speed.

Stand like a scale. Move like a wheel. If you drop one side, you can move. If you have equal pressure on both sides, you will be stuck. We often see one who has practiced hard for many years and yet is unable to perform any neutralizations and is always under the opponent’s control, and the issue here is that this error of double pressure has not yet been understood.

If you want to avoid this error, you must understand passive and active. In sticking there is yielding and in yielding there is sticking. The passive does not depart from the active and the active does not depart from the passive, for the passive and active exchange roles. Once you have this understanding, you will be identifying energies.

Once you are identifying energies, then the more you practice, the more efficient your skill will be. By absorbing through experience and by constantly contemplating, gradually you will reach the point that you can “follow your feelings and do as you please”, though the initial stage is to “discard ego, follow others”, which often seems to get misheard as “discard what is near, seek what is far”. To guard against such a mistake, remember: “Miss by an inch, lose by a mile.” You must understand all this clearly. That is why it has been written down for you.

此係武當山張三豐老先師遺論欲天下豪傑延年養生不徒作技藝之末也

(This text relates to the inherited theories of the founder Zhang Sanfeng of Mt. Wudang. He wished for all heroes to live long healthy lives and not merely gain skill.)

此論句句切要在心並無一字浮衍陪襯非有夙慧不能悟也先師不妄傳亦恐枉費工夫耳

(This essay contains one crucial sentence after another and does not have a single word that does not enrich and sharpen its ideas. But if you are not smart, you will not be able to understand it. The founder did not lightly teach the art, [not just because he was discriminating over accepting students,] but also because he did want to go to the effort only to have it wasted.)

長拳者如長江大海滔滔不絕十三勢者掤捋擠按採挒肘靠此八卦也進步退步左顧右盼中定此五行也合而言之曰十三勢也掤捋擠按卽坎離震兌四正方也採挒肘靠卽乾坤艮巽四斜角也進退顧盼定卽金木水火土也

Long Boxing: it is like a long river flowing into the wide ocean, on and on ceaselessly…

The thirteen dynamics are: warding off, rolling back, pressing, pushing, plucking, rending, elbowing, and bumping – which relate to the eight trigrams:

☴☲☷

☳ ☱

☶☵☰

and advancing, retreating, stepping to the left, stepping to the right, and staying in the center – which relate to the five elements. These combined [8+5] are called the Thirteen Dynamics. Warding off, rolling back, pressing, and pushing correspond to ☵, ☲, ☳, and ☱ in the four principal compass directions [meaning simply that these are the primary techniques]. Plucking, rending, elbowing, and bumping correspond to ☰, ☷, ☶, and ☴ in the four corner directions [i.e. are the secondary techniques]. Advancing, retreating, stepping to the left, stepping to the right, and staying in the center correspond to the five elements of metal, wood, water, fire, and earth.

–

十三勢歌

THIRTEEN DYNAMICS SONG

十三總勢莫輕視命意源頭在腰膝變轉虛實須留意氣遍身區不少痴靜中獨動動尤靜因敵變化是神奇勢勢存心撥用意得來不覺費工夫刻刻留意在腰間腹內鬆淨騰然尾閭中正神貫頂滿身輕利頂頭懸仔細留心向推求屈伸開合聽自由入門引路須口授工夫無息法自修若言休用何為準意氣君來骨肉臣想推用意終何在益夀延年不老春歌兮歌兮百四十字字真切亦無遺若不向此推求去枉費工夫噫嘆惜

Do not neglect any of the thirteen dynamics,

their command coming from your lower back.

You must pay attention to the alternation of empty and full,

then energy will flow through your whole body without getting stuck anywhere.

In stillness, movement stirs, and then once in motion, seem yet to be in stillness,

for being receptive to what the opponent is doing is where the magic lies.

Posture by posture, stay mindful, observing intently,

for if something comes at you without your noticing it, you have been wasting your time.

At every moment, pay attention to your waist,

for if there is complete relaxation within your belly, energy is primed.

Your tailbone is centered and spirit penetrates to your headtop,

thus your whole body will be nimble and your headtop will be pulled up as if suspended.

Pay careful attention in your practice

that you are letting bending and extending, contracting and expanding, happen as the situation requires.

Beginning the training requires personal instruction,

but it is your own unceasing effort that is the key to mastering the art.

Whether we are discussing in terms of theory or function, what is the constant?

It is that mind is sovereign and body is subject.

If you think about it, what is emphasizing the use of intention going to lead you to?

To a longer life and a longer youth.

Repeatedly recite the words above,

all of which speak clearly and leave nothing out.

If you pay no heed to those ideas, you will go astray in your training,

and you will find you have wasted your time and be left with only sighs of regret.

–

十三勢行工心解

UNDERSTANDING HOW TO PRACTICE THE THIRTEEN DYNAMICS

以心行氣務令沉著乃能收歛入骨以氣運身務令順遂乃能便利從心精神能提得起則無遲重之虞所謂頂頭見也意氣須換得靈乃有圓活之趣所謂變動虛實也發勁須沉者鬆淨專主一方立身須中正安舒支撐八面行氣如九曲珠無為不立運勁如百鍊鋼何堅不推形如捕兔之鵠神如撲鼠之貓靜如山岳動似江河蓄勁如開弓發勁如放箭曲中求直蓄而後發力由脊發步隨身換收卽是放斷而復連往復須有摺疊進退須有轉換極柔輭然後堅硬能呼吸然後能靈活氣以直養而無害勁以曲經而有餘心為令氣為旗腰為纛先求開展後求緊湊乃可臻於縝密矣

Use your mind to move energy. You must get your posture to settle. Your energy will then be able to collect into your bones. Use energy to move your body. You must get your movement to be smooth. Your body can then easily obey your mind.

If you can raise your spirit, then you will be without worry of being slow or weighed down. The Thirteen Dynamics Song calls for the whole body to be nimble and the headtop to be pulled up as if suspended. The mind must perform alternations nimbly, and then you will have the qualities of roundness and liveliness. The Thirteen Dynamics Song says to pay attention to the alternation of empty and full.

When issuing power, you must sink and relax, concentrating it in one direction. Your posture must be straight and comfortable, bracing in all directions.

Move energy as though through a winding-path pearl, penetrating even the smallest nook. Wield power like tempered steel, so strong there is nothing tough enough to stand up against it.

The shape is like a falcon capturing a rabbit. The spirit is like a cat pouncing on a mouse.

In stillness, be like a mountain, and in movement, be like a river.

Store power like drawing a bow. Issue power like loosing an arrow.

Within curving, seek to be straightening. Store and then issue. Power comes from the spine. Step according to your body’s adjustments. To gather is to release. Disconnect but stay connected.

In the back and forth [of the arms], there must be folding. In the advance and retreat [of the feet], there must be variation.

Extreme softness begets extreme hardness. Your ability to be nimble lies in your ability to breathe.

By nurturing energy with integrity, it will not be corrupted. By storing power in crooked parts, it will be in abundant supply.

The mind makes the command, the energy is its flag, and the waist is its banner.

By seeking first the gross movement and then the finer details, you will be able to attain a refined level.

又曰先在心後在身腹鬆氣歛入骨神舒休靜刻刻在心切記一動無有不動一靜無有不靜牽動往來氣貼背歛入骨內固精神外是安逸邁步如貓行運勁如抽絲全神意在精神不在氣在氣則滯有氣者無力無氣者純剛氣如車輪腰如車軸

It is also said:

First in your mind, then in your body.

Your abdomen relaxes completely and then energy collects into your bones. Let your spirit be comfortable and your body calm.

At every moment be mindful, always remembering: if one part moves, every part moves, and if one part is still, every part is still.

As the movement leads back and forth, energy sticks to your back, gathering in your spine. Inwardly bolster spirit and outwardly show ease.

Step like a cat and move energy as if drawing silk.

Your whole mind should be on your spirit rather than on your energy, for if you are fixated on your energy, your movement will become sluggish. Whenever your mind is on your energy, there will be no power, whereas if you ignore your energy and let it take care of itself, there will be pure strength.

The energy is like a wheel and the waist is like an axle.

–

打手歌

PLAYING HANDS SONG

掤捋擠按須認真上下相隨人難進任他聚力來打咱牽動四兩撥千斤引進落空合卽出粘連黏隨不丟頂

The techniques of ward-off, rollback, press, and push must be taken seriously.

With proper coordination between upper body and lower, the opponent will not find a way in.

It does not matter even if he uses his full power when he attacks me,

for I will tug with a mere four ounces of force to divert his of a thousand pounds.

Having thus guided him in to land on nothing, I then close in and shoot him out.

I stick, connect, adhere, and follow, neither coming away nor crashing in.

又曰彼不動己不動彼微動己先動勁似鬆非鬆將展未展勁斷意不斷

It is also said:

If he takes no action, I take no action, but once he takes even the slightest action, I have already acted.

My power seems to be relaxed but not relaxed, about to extend but not fully extending. Although the power finishes, the intent of it continues.

–

十三勢名目

POSTURE NAMES FOR THE THIRTEEN DYNAMICS SOLO SET

攬雀尾

[1] CATCH THE SPARROW BY THE TAIL

單鞭

[2] SINGLE WHIP

提手上勢

[3] RAISE THE HANDS

白鶴亮翅

[4] WHITE CRANE SHOWS ITS WINGS

摟膝拗步

[5] BRUSH PAST YOUR LEFT KNEE IN A CROSSED STANCE

手揮琵琶勢

[6] PLAY THE LUTE

進步搬攔捶

[7] ADVANCE, PARRY, CATCH, PUNCH

如風似閉

[8] SEALING SHUT

抱虎歸山

[9] CAPTURE THE TIGER AND SEND IT BACK TO ITS MOUNTAIN

攬雀尾

[10] CATCH THE SPARROW BY THE TAIL

肘底看捶

[11] BEWARE THE PUNCH UNDER ELBOW

倒輦猴

[12] RETREAT, DRIVING AWAY THE MONKEY

斜飛勢

[13] SLANTED WINGS

提手上勢

[14] RAISE THE HANDS

白鶴亮翅

[15] WHITE CRANE SHOWS ITS WINGS

摟膝拗步

[16] BRUSH PAST YOUR LEFT KNEE IN A CROSSED STANCE

海底針

[17] NEEDLE UNDER THE SEA

扇通背

[18] FAN THROUGH THE BACK

撇身捶

[19] TORSO-FLUNG PUNCH

卻步搬攔捶

[20] STEP BACK, PARRY, CATCH, PUNCH

上勢攬雀尾

[21] CATCH THE SPARROW BY THE TAIL

單鞭

[22] SINGLE WHIP

雲手

[23] CLOUDING HANDS

高探馬

[24] RISING UP AND REACHING OUT TO THE HORSE

左右分腳

[25] KICK TO THE SIDE – RIGHT & LEFT

轉身蹬腳

[26] TURN AROUND, LEFT PRESSING KICK

進步栽捶

[27] ADVANCE, PLANTING PUNCH

翻身撇身捶

[28] TURN AROUND, TORSO-FLUNG PUNCH

反身二起腳

[29] TURN AROUND, DOUBLE KICK

上步挫捶

[30] STEP FORWARD, SCRAPING PUNCH

雙風貫耳

[31] DOUBLE WINDS THROUGH THE EARS

披身踢腳

[32] DRAPING THE BODY, LEFT KICK

轉身蹬腳

[33] SPIN AROUND, RIGHT PRESSING KICK

斜單鞭

[34] DIAGONAL SINGLE WHIP

野馬分鬃

[35] WILD HORSE’S MANE GOES SIDE TO SIDE

玉女穿梭

[36] MAIDEN SENDS THE SHUTTLE THROUGH

單鞭

[37] SINGLE WHIP

雲手下勢

[38] CLOUDING HANDS, LOW POSTURE

金雞獨立

[39] GOLDEN ROOSTER STANDS ON ONE LEG

倒輦猴

[40] RETREAT, DRIVING AWAY THE MONKEY

斜飛勢

[41] SLANTED WINGS

提手上勢

[42] RAISE THE HANDS

白鶴亮翅

[43] WHITE CRANE SHOWS ITS WINGS

摟膝拗步

[44] BRUSH PAST YOUR LEFT KNEE IN A CROSSED STANCE

海底針

[45] NEEDLE UNDER THE SEA

扇通背

[46] FAN THROUGH THE BACK

上勢攬雀尾

[47] STEP FORWARD, CATCH THE SPARROW BY THE TAIL

單鞭

[48] SINGLE WHIP

雲手

[49] CLOUDING HANDS

高探馬

[50] RISING UP AND REACHING OUT TO THE HORSE

十字擺連

[51] SINGLE-SLAP SWINGING LOTUS KICK

摟膝指𦡁捶

[52] BRUSH PAST YOUR LEFT KNEE, PUNCH TO THE CROTCH

上勢攬雀尾

[53] STEP FORWARD, CATCH THE SPARROW BY THE TAIL

單鞭下勢

[54] SINGLE WHIP, LOW POSTURE

上步七星

[55] STEP FORWARD, BIG-DIPPER POSTURE

退步跨虎

[56] RETREAT, SITTING-TIGER POSTURE

轉腳擺連

[57] SPIN AROUND, DOUBLE-SLAP SWINGING LOTUS KICK

彎弓射虎

[58] BEND THE BOW TO SHOOT THE TIGER

上步攬雀尾

[59] STEP FORWARD, CATCH THE SPARROW BY THE TAIL

合太極

[60] CLOSING POSTURE

– – –

[Included below is an early article introducing the manual to the martial arts community.]

王宗岳先生傳

A BIO OF WANG ZONGYUE

顧留馨

by Gu Liuxin

[published in 國術聲 Martial Arts Voices, Vol. 3, Issue #10, Dec 20, 1935 (though written in 1931)]

王宗岳先生,淸乾隆時山西人也。少時經史而外,黃帝老子之書及兵家言,無書不讀,兼通擊刺之術,槍法其尤精者也。先生從事拳技近數十年,嘗作太極拳論數篇,文長不過千字,而太極拳之精微所在,已包蘊無餘,百餘年來,太極拳之架式,幾經變更,獨其眞意猶未絕傳者,端賴先生著論之功也。公元一七九一年(歲辛亥,乾隆五十六年)先生將槍法集成為訣,而明其進退變化之法,名曰陰符槍。蓋先生精通三敎之書,深觀於盈虛消息之機,熟悉於止齊步伐之節,簡練揣摩,自成一家者也。書成,謂其友曰:「予本不欲譜,但悉心於此中數十年,而始少有所得,不以公之天下,恐此道將與吾身而俱沒也」!槍譜分陰符槍總訣六則,上平勢七則,中平勢十三則,下平勢十一則,川袖,挑手,穿指,搭外,搭裏十三則,陰符槍七絕四首,其槍練法,亦是以意會氣,積柔成剛,粘隨不脫,疾若風雲,與太極拳同其功用。

世傳太極拳係武當丹士張三豐所傳,假託附會,誕妄不足信。范生所若少林武當攷中辨之詳矣。惟太極拳理深微而無不包,然亦含潭而不易曉解,若無先生著論以供後學之揣摩,此術恐早已湮沒失傳如廣陵散矣!

宗岳先生實為太極拳門之馬鳴龍樹也。惜其生卒年月已不可考,陰符槍譜敍僅記其當乾隆乙卯年(乾隆六十年,公元一七九五年)曾館於汴云。

留馨按:宗岳先生去今纔百二三十年,其行誼年月,已不可攷,近人許禹生誤以山西人王宗岳卽為關中人之王宗,(見許著太極拳勢圖解第九頁)陳微明則臆測宗岳先生為淸初時人,(見陳著太極拳答問第一頁)傳說紛紜,莫衷一是。先生為有淸一代拳宗,今之習太極拳者,莫不奉其遺論為圭臬,然其名不見於史乘,遂令後人不知先生究為何許時人,良可慨也!近唐范生君在北平廠肆購得舊抄本陰符槍譜一冊,為前此所未見,槍法理論,不離太極拳之原則。有敍一篇,因以略見先生之為人,而得斷定先生為乾隆時人,實為太極拳門授受源流上之一大發現也。槍譜後並附有太極論等如今世所傳者,因疑太極拳論亦為先生作品,假託張三豐所著以堅世人之信仰焉。

二十年十月十七日。

Wang Zongyue was from Shanxi and lived during the reign of Emperor Qianlong [1736–1795]. When he was young, he went beyond the standard study of the Confucian classics and historical texts, reading also such books as the Yellow Emperor’s Medicine Classic and the Daodejing, as well as the works of military strategists, basically any book he could get his hands on. He also became thoroughly versed in fighting arts, of which he was especially skillful in spear methods. Based on his many decades of martial experience, he wrote several Taiji Boxing texts. Comprised of just over a thousand words, the profundities of the art are expressed in his writings perfectly and completely. Although the Taiji Boxing solo set has gone through many modifications over the course of the last century, his transmission alone has stood the test of time, so much so that practitioners rely entirely upon his work in order to gain true understanding.

In 1791, he “presented his spear art in a collection of instructions, illuminating his methods of advancing, retreating, and adapting.” He named his method “Conceal & Reveal Spear”. Based on his thorough understanding of Confucianism, Buddhism, and Daoism, he had a keen sense for the principle of waxing and waning forces, as well as for obtaining the best position and timing to take advantage of them. Refining his ideas into compact and yet comprehensive statements, he had created his own art. After completing the book, he told his friend: “I didn’t originally intend to write a manual. However, after decades of meticulous practice, I feel I’ve obtained something worthwhile, and if I don’t share it with the world, there might never be anybody else who knows these skills.” Or basically: “I’m worried this special thing I’ve invented will die with me.”

His manual is divided into six parts: [1] General Principles (six sections); [2] High Attacks (seven scenarios); [3] Mid-Level Attacks (thirteen scenarios); [4] Attacks from Below (eleven scenarios); [5] Through the Sleeve, Carrying Hand, Threading Finger, Connecting Outward, Connecting Inward (seventeen sections); [6] Four Verses of Seven-Character Lines. His spear principles have a Taiji-like sensibility of using intention to guide energy and of accumulated softness becoming hardness. His very advice to “stick and follow without disconnecting, be as sudden as winds and storms” [in General Principles, part 2] is effectively the same as in Taiji Boxing.

It has been said for generations now that Taiji Boxing was passed down from the elixirist Zhang Sanfeng of Wudang. This is merely a flimsy attempt to claim legitimacy for one’s art through some name-dropping, and is not remotely believable, as Tang explained in his Investigation of Shaolin & Wudang [published the previous year]. Taiji Boxing theory is both penetrating and all-encompassing. However, its depths are not easy to fathom. Without the help of Wang’s writings giving later generations something to work with, this art would probably already be as lost as the Guangling Melody.

He is for the Taiji boxing art like an Ashvaghosha or Nagarjuna [tremendously influential writers of Buddhist literature]. It is a pity that we cannot pin down the dates of his birth and death. All we have is the date of 1795 for when that preface about him was written, and that it was written in Kaifeng. Wang died somewhere around a hundred and twenty or thirty years ago, but we cannot figure out exactly when or where. Xu Yusheng in his 1921 manual mistakenly thought that the Wang Zongyue of Shanxi was actually a Wang Zong of Shaanxi. Chen Weiming in his 1929 book puts forth the view that Wang Zongyue lived during the early rather than middle Qing Dynasty. Opinions are varied and it is hard to know who is right.

Wang was the founder of a Qing era martial art. Modern Taiji Boxing practitioners all accept his writings as the gold standard of instruction, and yet his name is nowhere to be found in any historical records, resulting in later generations having no context in which to place him, truly a pity. Recently, Tang Hao purchased from Beijing Store #4 an old handwritten booklet of the Conceal & Reveal Spear Manual, previously unseen, containing spear methods and theory, which do not depart from Taiji Boxing principles. Its preface paints a refreshing picture of Wang as a person, not merely a soulless figure who “lived during the reign of Emperor Qianlong”. This is a great discovery concerning the source of Taiji teachings. At the end of the spear manual is also included the Taiji Classics that have been passed down to this day. Many have resisted the idea that Wang is the author because they are so wedded to the idea that these are the writings of Zhang Sanfeng.

- Oct 17, 1931

不佞所編武藝叢書,第四種原定少林武術史料。以付印時續有發見,現正覓求原書輯入,以期內容充實。茲將第四種易為王宗岳陰符槍譜及太極拳經,明歲一月間可與其他三種同時出版。內附拙著王宗岳考,約五千言,於其時代,籍貫,身世,思想,著作,武藝,發明,均有闡發,先為附告於此。留馨先生斯作,存不佞處者凡四載餘,茲為披露本刊,以餉讀者。

唐豪附識。

A note by Tang Hao:

I have written a book about this material, following up on a volume I produced about the history of Shaolin. Now is the time for it and at last it is finished. I have given it the rather obvious title of On the Conceal & Reveal Spear Manual and Taiji Boxing Classics of Wang Zongyue. It will appear early next year [published May, 1936]. My analysis of Wang Zongyue is a book of about five thousand words, discussing when he lived, where he was from, his experience, ideas, writings, skills, creations, all of which I scrutinize in detail, and which I am now mentioning publicly for the first time. Following Gu’s introduction of the subject here, which I have been keeping for this moment for the last four years, I hereby announce the book for your interest… (Voilà)

–

–

–